Perspectives Posted on 2019-02-19 12:39:13

Gender and pastoralism

Keywords

Authors

A. Rota (1)*, S. Sperandini (2) & O. Mundy (3)

(1) Lead Technical Specialist, Livestock Development, Sustainable Production, Markets and Institutions Division. International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), Via Paolo di Dono, 44, 00142 Rome, Italy

(2) Consultant, Gender and Social Inclusion Team, International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD)

(3) Environment and Climate Analyst, International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD)

* Corresponding author: a.rota@ifad.org

The designations and denominations employed and the presentation of the material in this article do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the OIE concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers and boundaries.

The views expressed in this article are solely the responsibility of the author(s). The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by the OIE in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned.

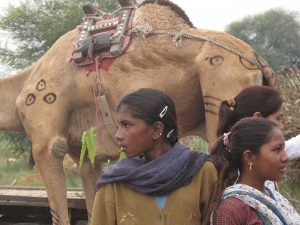

While men and boys are away tending the herd, pastoralist women are responsible for collecting fodder to supplement the feed of those livestock kept close to the homestead. They look after pregnant stock, and then their calves, kids and lambs, and take care of sick animals that cannot keep up with the main herd [2]. They milk lactating animals and make sour milk and butter, which are important parts of the diet of many pastoralist families. They also sell these products at markets.

©IFAD/FAO/WFP/M.Tewelde

It is important to note that there is huge diversity among ethnic groups and their production systems, as to who owns the animals, who takes care of them, who sells the products and who controls the income.

Pastoralist women face enormous challenges, which are mainly linked to the complex gender relationships between pastoralist women and men [3]. Inequality affects their roles and responsibilities, and plays a major part in traditional customs, property rights, decision-making, and the use and control of income, assets, resources and services [4]. Such inequalities restrict women’s development potential and limit the opportunities and economic growth of the entire family.

In 2010, more than 100 pastoralist women from 31 countries gathered in the small village of Mera

Women pastoralists want to take full advantage of development opportunities and capture the benefits of economic empowerment, becoming real agents of transformation for their society. In 2010, more than 100 pastoralist women from 31 countries gathered in the state of Jharkhand in India, in the small village of Mera, and demanded more opportunities, including better access to productive resources, markets, technologies, knowledge and services, while still retaining their culture and traditional lifestyle. This was documented in the Mera Declaration [4, 5].

‘This is our right and it is by remaining pastoralists that we can be of greatest service to the entire human community’ (from the Mera Declaration, sponsored by IFAD)

Women and animal health interventions

Effective management of animal health, especially the control of animal and zoonotic diseases, is the main challenge facing pastoral communities. Access to reliable veterinary care, inputs and services is made difficult by the mobility of pastoral livestock herds, which are often located in remote areas, while pathogens and the insect vectors that carry them can be spread with the movement of people and animals [6].

Women play a hugely important role in disease control and are very knowledgeable about disease symptoms. They are often the first to identify livestock diseases and treat sick animals. For example, when calves are suckling, they are in close contact with both cow and calf, and can observe any sudden drop in milk production, which could indicate illness.

Governments and development organisations have come to appreciate the importance of including women in animal health interventions. Evidence in the field shows that, when pastoralist women receive adequate training and technical support, they play a key role as community animal health workers and paraveterinarians [7]. They are crucial in reaching out to other women in their community, passing on valuable knowledge and skills and acting as powerful development drivers. Therefore, it is essential to recognise the role that women play in livestock production in pastoral areas. National policies, development projects and livestock service-delivery planning should take women’s roles, needs and knowledge into full consideration, leading to gender empowerment, social inclusion and gender equality.

The IFAD-funded Rural Microfinance and Livestock Support Programme in Afghanistan trained female facilitators as community-based animal health workers. They now provide animal health services to their community, teach livestock keepers how to vaccinate their animals and share information and technologies with other women.

http://dx.doi.org/10.20506/bull.2018.2.2864

References

- Rota A. & Sperandini S. (2012). – Livestock and pastoralists. International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), Rome.

- Rota A. & Sperandini S. (2010). – Gender and livestock: tools for design. International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), Rome.

- Flintan F. (2008). – Women’s empowerment in pastoral societies. International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Gland, Switzerland & World Initiative for Sustainable Pastoralism (WISP), Nairobi, Kenya.

- Rota A., Chakrabarti S. & Sperandini S. (2012). – Women and pastoralism. International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), Rome.

- Women Pastoralists (2012). – Mera Declaration of women pastoralists. International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Gland, Switzerland.

- Amuguni H.M. (2001). – Promoting gender equity to improve the delivery of animal health care services in pastoral communities. African Union/Interafrican Bureau for Animal Resources (AU–IBAR), Nairobi, Kenya.

- Mathias E. (2005). – The role of ethnoveterinary medicine in livestock production. In WAAP book of the year – 2005: a review on developments and research in livestock systems (A. Rosati, A. Tewolde & C. Mosconi, eds). Wageningen Academic Publishers, Wageningen, the Netherlands, 257–269.